Promethean Ambitions – Chapter 1 & 2 (~p.62)

Jun 10, 2018

12 min read

0

2

0

The following is a summary of William Newman’s book on the history of alchemy, Promethean Ambitions. Due to the overwhelming information offered in the book, I will divide summaries into several portions rather arbitrarily, the first of which deals with the longstanding contest between man and nature from the antiquity, and three things are discussed here. I will start with the differing opinions about the various forms of art and how they relate to nature, arriving at Zosimos’ claim to replicate nature, i.e. proto-alchemy stage. Second, the argument against the view that alchemy as not only a perfective art but also equivalent to nature is advanced by Avicenna. Here, the discussions about the substantial forms and a debate on juxtaposition and mixture are analyzed. A further rejection of alchemy as a genuine replication of nature is then made by Albertus Magnus in the 13thcentury.

Chapter One: Imitating, Challenging and Perfecting Nature

Although we commonly conceive of science as an antinomy of nature, the Greeks viewed the fine arts to be overstepping the realm of nature. The sculptor, Myron, made a statue of a cow that seemed so full of life that it fooled even a herdsman. The painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius are said to have fooled one another by their mimetic skills displayed in their paintings. The ancient craftsman, Daedalus, impressed even Aristotle, who reports that the artist made a self-moving statue of Aphrodite that owed its motive capacity to quicksilver hidden within. Such figures demonstrate the classical ambivalence in the meaning of artesand technai,which we now distinguish them as arts and technology, respectively. Aristotle, for example, viewed painting and sculpture as technaialong with agriculture, building and medicine amongst others, much in the same way as poetry to him was. Indeed, to Aristotle, an art simply meant a reasoned state of capacity to make, i.e. the ability to produce in a methodical and clever way. Whereas painting and sculpture were thought to be a mimicry of nature as their primary goal, an art was generally perceived to be acquired by imitating various aspects of the natural world. Democritus, for instance, expressed how men learned the art of weaving from spiders and that of singing from birds. The underlining notion in all these stories about learning from nature is the idea that the human ingenuity owes its origin to the production of simulacra of nature. However, even though an artifice mirrors the performance of things found in nature, i.e. a saw is like a jawbone and the process of baking bread is like eating and digesting grain, no one actually argued that a saw is a jawbone or the bread making is identical to the assimilation of food in the body.

Plato, in his Republic, contrasted the carpenter to the painter, saying that the former imitates the work of nature by mimicking the ideal form of a bed, while the latter only copies the imitation of that form. Artists, then, are said to be performing some sort of deception in making us believe what is painted as the real thing, e.g. like the sculptor who made a statue of a cow. Plato deems art as trickery and holds its mimetic nature in disdain. Aristotle, too, makes a distinction between the product of nature and the product of artifice in Physicson the basis of the fact that the natural products have an innate principle of motion and thus able to put themselves into motion without an external help, whereas those of artifice are static and do not possess any inherent tendency to move. Aristotle, however, explains that art can function in two different ways: the arts can 1) either carry things further than Nature can, or 2) only imitate Nature. In other words, arts can be interpreted in two distinct ways, i.e. as a perfectiveart and an imitativeart. The former tries to perfect natural processes and bring them to a state of completion found nowhere in nature, while the latter merely imitates nature without fundamentally altering it. The art of the first kind was championed by medical practices, since the physicians did not generally lead the human body to an unnatural state, but merely brought it to its natural condition of health by eliminating impediments. In this sense, medicine can be said to be the servant of nature, as Galen called it, and perfective as it brought nature to an end which would not otherwise be realized.

Contrary to the Aristotelian conception of perfective art, however, the Neoplatonic belief states that immaterial forms exist apart from matter, and the latter receives its qualitative characteristics from the forms. Since artists get their ideas from the superior immaterial world of forms, shaping matter and imposing the forms on matter is seen to be at least improving the matter, if not perfecting it. In this sense, artists try to mirror not the things actually found in material world but rather the forms themselves. Hence, molding the matter according to these unfiltered forms bypasses the temporal constraints that are needed for things to naturally come into a certain shape and being, and such an act is likened to the acceleration of natural processes by directly bringing down the forms, so to speak, from the superior world of forms.

For Aristotle, however, it is one thing to improve uponnature in the sense of making something better than nature itself or even outdoing it, and quite another to improve nature itself, which just means to make nature itself better. These can be said to be mimetic in the sense that they too imitate the natural processes but carry it further than nature itself would. However, purely imitative art does not bring a product into its perfection or to a natural state. Painting and sculpture belong to this type of art since they have nothing to do with perfecting nature in the Aristotelian sense. Indeed, no matter how perfect and how natural the statue of a cow or a painting of a plant it is, neither of them can compete with nature, as they lack in the internal constitution of change.

Mechanical Problems, a pseudo-Aristotelian work, claims that marvelous phenomena can be produced either when we do not know the cause of a thing or when art is induced to act against nature. What the latter means by ‘acting against nature’ is that, according to the Aristotelian system of the sub-lunar world, all things are composed of four elements, fire, air, water and earth and they have their own natural place to settle. However, some art contrives nature to work contrary to their natural tendencies, i.e. lifting a heavy body or flying an airplane, for instance, and to that extent, arts or mechanics work againstnature. This type of art differs from merely mimetic arts mentioned above, i.e. painting and sculpture. For the latter produced changes that were irrelevant or superficial to the inner principles of nature, but mechanics worked directly in opposition to what nature is supposed to do. However, all three arts have this in common, that is, that they are limited to the production of artificialia– the iron lever could not breed new levers any more than a painted horse cold assuage its hunger by eating its painted hay. However, one thing is different from the other types of mimetic arts – namely, in that mechanics is no longer a mere mimicry of nature but by forcefully contriving nature to act in different ways it tries to achieve an actual triumph over nature.

Ancient Alchemy and the Relationship between Art and Nature

The definition of alchemy was ambiguous – alchemy was concerned with reproducing natural products in all their qualities and not merely to make a superficial simulation, as in painting and sculpture. Alchemy then was a perfective art, and not a memetic art, that was like medicine, but also differed from medicine in the sense that medicine aimed to reinstate or acquire a physical state (health) while alchemy was concerned with creating physical objects.

According to a historian of late antique religion, A. J. Festugière, the outlook of ancient/proto-alchemy as a decorative art began to change in the period between 200 B.C.E. and 100 C.E., when it started to mention about sympathies and antipathies between different substance. Up until then, alchemy was concerned with technical recipes used in embalmment and making objects similar to or even better than their natural counterparts. However, when they began discussing about the inner constitution of things and their relationships with one another, it was now wanting explanation and subject to philosophical scrutiny.

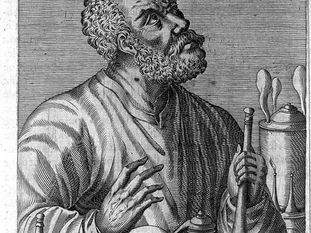

Zosimos, a native of Panopolis in upper Egypt (circa. 300 C.E.), who was well-versed in the works of Hermes Trismegistus and Gnostic literature, tried to explain the technological basis already used for embalmment in terms of philosophical notions from the late Stoic philosophy. Zosimos viewed alchemy as not simulating natural products but as providing the means by which nature itself can pass from an imperfect state to a regenerate one. Zosimos’ alchemical commitment can be seen in the visual descriptions of distillation and sublimation apparatus given by Zosimos. He explains evaporative process in nature as the conversion of a body into a semi-material spirit, or pneuma. In accordance with the Stoic philosophy of matter, pneumais here equated with the principle of brilliance, activity and life itself. A still or sublimatory thus acquires a profound soteriological importance for the alchemists, as it allows pneumato be liberated from its material prison.

Zosimos’ apparatus

Chapter Two: Alchemy and the Art-Nature Debate

Was art always limited to the imperfect mimicry of nature, or could human beings genuinely recreate natural products? If the latter, then alchemists could assert the power of God to create beings where none had been there before. If they could replicate nature in its entirety, could they also replicate life itself, perhaps even making it betterthan the natural life?

The Persian philosopher, Avicenna (Ibi Sīnā, d. 1037), waged what was probably the most influential attack on alchemy ever made in his book, Book of Remedy. Avicenna makes two very powerful arguments against alchemy: 1) Art is weaker than nature and does not overtake it, however much it labours – the art is naturally inferior to nature because of its imitative nature, and therefore it cannot make a product that genuinely measures up to its natural exemplar. 2) Species of metals cannot be transmuted – Avicenna here stresses that the mere fact of belonging to a single genus (metallic substance) does not mean that the individual species (the different metals) can be transmuted among themselves.

The basis of Avicenna’s rejection of alchemy as possessing the power that is equal to divinity arises from his core philosophy adhering to Aristotle’s theory of mixture that genuine mixture (mixis) is distinct from mere juxtaposition of tiny particles (synthesis). In order for juxtaposition or aggregates of particles to become homogenous mixture, a new form must be imposed onto the matter, i.e. the form of the mixture (forma mixti), which would produce a single new substance (forma substantialis) out of the four elements and is distinguished from the previous juxtaposition. Avicenna also argued for the belief in a dator formarum(giver of forms), which explains that this new substance-changing form would not emerge out of matter, but is imposed from without by the celestial intelligences, the world of forms, as it were. Further, Avicenna believed that the primary qualities, hot, cold, dry and wet did not combine to form a mixed body, but merely set up the precondition that allowed the imposition of a new substantial form by the dator formarum. A substantial form has a specific role to play in the explanatory system of mixture, or homogenous substance. For example, what is it that makes a human a human, instead of a mere heap of elements? It is the substantial form, Avicenna argued, that unites the elements to impart an identity and have an individual belonging to a recognizable species. Due to the role of the substantial form as making an individual belong to a specific species, the term specific form (forma specifica)was also used for the substantial form. The true nature and the substantial form of a thing is reserved to God and the celestial intelligences and cannot be known to man nor can its specific differences be influenced by artificial means. A further denial of alchemy is proposed by a Muslim historian Ibn Khadūn, who observed that if what alchemists claim were true, then they could produce a new substance/metal in a matter of weeks. This implies that their methods are more effective than those of nature itself, which is impossible. In this way, Ibn Khadūn augments the view held by Avicenna by stating that such a work must be attributed to supernatural powers, and that the products of alchemical success can only be viewed as miracles or acts of divine grace, or as sorcery.

Yet another great Arabic Aristotelian philosopher, Averroes, argues against the legitimacy of alchemy. Averroes argued that just as beings created spontaneously cannot reproduce by sexual means, and just as what is generated sexually and what is generated spontaneously are essentially different, so is it impossible for a single specific form to have diverse materials upon which it can act and produce beings of the same species. He continues to argue that just as one and the same thing cannot be made both by art and nature, so also the causes of natural entities cannot be different and yet agree in species and form.

During the 13thcentury, since many Arabic texts had been translated into Latin by the late 12thcentury, many scholastics joined the debate on the basis of Aristotle’s Meteorologyand since attack against alchemy by Avicenna in De Congelatione,which was at the time was believed to be the work of Aristotle, fell short to say that the artificial transmutation of metals could be possible if they were first reduced into their “prime matter” – the undifferentiated substrate of all things according to Aristotelian physics. Albertus Magnus is another figure who argued against the genuinereplicationof nature by alchemy. He says that only four types of transmutation are possible: 1) by means of medicinal operation of the drug theriac, where the ingredients of a mixture retain their identity and operation, while also working in unison to produce a new effect, 2) by means natural process of fire or evaporation, where a body is dissolved into its components, 3) by means of alchemy, and 4) in case of spontaneous generation. The alchemical transmutation occurs through the stripping off of properties and the imposition of others through liquefaction, cibation, sublimation and distillation. However, Albert argues, alchemists do not give substantial forms because one cannot find the properties comprising the species in the things produced thus. Furthermore, alchemical gold is consumed in the fire more easily and the other alchemical stones also do not last as long as the natural ones of that species. This is because they do not have the specific form, and so nature has denied them the virtues that are given with the specific form for the conservation of the same. Indeed, Albert’s claim is that the alchemists can only strip off transient accidents and replace them with equally superficial ones. This fact renders the alchemical products the inability to resist the dissolutive power of fire. The only possibility for a transmutation of metals for Albert is if it is done in the same way as doctors would approach their patients, that is to say, the alchemists can first cleanse and purify the old metal just as a doctor employs emetics and diaphoretics to purge his patient. By this method, the elemental and celestial powers in the metal’s substance are strengthened, and the purged metal can receive a new and better specific form from the celestial bodies. But this is not a true transmutation of a substance since the alchemists have only removed one specific form and prepared the way for the new one to be received.

In what has been noted, Newman begins his book by trying to determine the rise of alchemical practices in the history of science while extracting the philosophical content involved in what he called proto-alchemy. He illustrates the classical dichotomy between art and nature with an especial focus on whether arts can transcend nature in the sense that arts improve upon nature as opposed to merely helping nature to reach its natural sequence, i.e. mimetic or perfective arts. He then moves onto introducing a prolific alchemist in the 4thcentury C.E., Zosimos, whose late Stoic philosophy encouraged him to pursue unveiling the inner workings of the natural phenomena rather analogously, equating the evaporation process of water with liberation of imprisoned spiritual substance from its material counterpart. However, the theories of alchemical transmutation were met with a number of hostile views during the 13thcentury, when many of the Arabic texts and commentaries on Aristotle’s works such as Physicsand Meteorologywere being translated into Latin. Among the major criticisms against alchemy and its claim to outdo nature came from the philosophers such as Avicenna, Averroes and Albertus Magnus, who all argued that the art is of necessity inferior to nature, and as such, it cannot replicate nature. Further, such product as created by alchemical means does not possess the forma substantialisthat can be only given by a pure activity, i.e. God, or divinity. Hence, while alchemy may strip away the properties that are accidental to a thing’s being, it is not possible for an alchemist to substantially change, i.e. transmute, a given substance into a whole new substance. For even with the inter-species transmutation, it requires a new specific form which cannot be produced by human means.

This has been a summary only of the beginning of the book (the chapter 1 and the part of the chapter 2) where it primarily deals with the historical origin of alchemy and the attacks against alchemical claim that it can create something that was not there much faster than nature can. I will next discuss about the proponents and supporting views for alchemy.

[Newman, William R. Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005.]